All Politics Is National

How state and local elections fail us, and what we can do about it.

Reuters

ReutersIf there is a dominant conceit among commentators on American politics, it is that national politics are somehow artificial when compared with the rich, grounded reality of our state and local democracies. Every day on cable news, Washington politicians are castigated for being "out of touch" while local officials are treated like they have their fingers on the pulse of popular sentiment. Tip O'Neill's famous quote -- "All politics is local" -- is treated as if it had oracular profundity.

But the veneration of local politics is based on a basic misunderstanding of how voters behave. For all the flak that national elections get, they have real meaning. Voters are presented with a clear choice between candidates from two very different and competitive parties, whose contrasting positions on key issues makes the decision about which party and candidate to support relatively easy for most. State and local elections look very different. Battles for control of legislatures are frequently uncompetitive, parties regularly do not take stances on key issues, and voters are poorly informed about the issues at stake and would struggle to pick most candidates out of a lineup.

What often ends up happening in state and local elections is that a voter casts a ballot for a candidate from the party whose national stances she agrees with. For all the paeans one hears to "our federalism" from politicians and judges, the paradoxical truth is that voters do not actually know more about elections and issues in their backyards. They know less.

When you think about it, this makes sense. We are too busy and the individual benefits are too small for most of us to invest time and effort in learning much about issues or candidates for county legislature or even Congress before we vote. In order for elections to be meaningful, we need help.

In federal elections, party labels provide us with that help. Particularly in these polarized times, knowing that a congressional candidate is a Democrat or Republicans tells us almost everything we need to know about how she'll vote in Congress. Furthermore, because the parties are pretty consistent over time, we can develop "running tallies" of observations about what Democrats and Republicans have done while in office that can guide us in the voting booth. As long as some people notice each political event, the electorate as a whole can develop "macropartisan" running tallies that shift in response to the successes and failures of each party, and an uninformed electorate can behave like a more informed one. Not perfectly -- the electorate can be myopic, influenced by irrelevant information and biased in how it interprets data -- but better than you would think if you only looked at survey data that shows that many Americans know little about politics. As a result, federal officials can be held somewhat accountable for their actions. If the economy is doing badly or the government does something unpopular, the party in power will have to pay a political price.

In state and local elections, we rely on party labels too, but they do less work for us. The reason is that even when the election is for local office, we still rely on national party labels. There is a "mismatch" between the level at which party identification is created and the level of government at issue in the election.

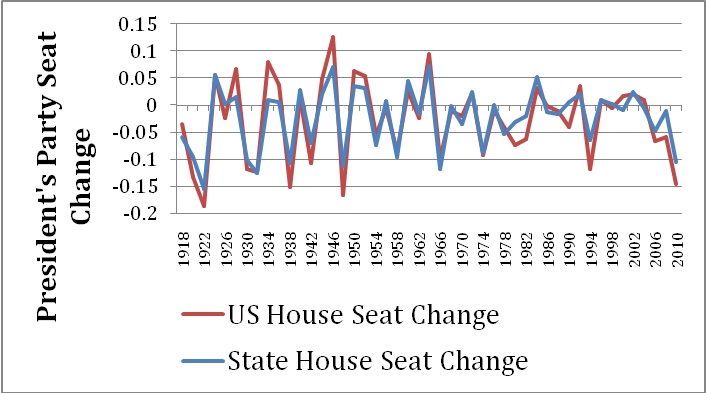

Look at this chart, which appears in my new paper with Chris Elmendorf (thanks to Steve Rogers, who built the chart):

The chart shows that when a party does well in federal elections, it does almost equally well in state elections. Most votes in state legislative elections turns on impressions we develop about national politics -- we punish and reward state officials largely for what Congress and the president do, rather than for what they do themselves. The same is true in city council elections in big cities. High-profile state and local candidates can successfully develop a brand for themselves that permits them to outperform their party (like Dave Freudenthal, the recent Democratic governor of Idaho, and Michael Bloomberg, who became mayor of New York City as a Republican), but down-ballot results are almost entirely determined by national party preference.

One important consequence is that state and local legislative elections are frequently uncompetitive. For instance, neither house of the Massachusetts legislature has been controlled by the Republicans since 1946 (and it hasn't been close). The reason is not that Democratic governance of the state has been unwaveringly brilliant -- the success of Republican candidates for governor like William Weld and Mitt Romney belies this -- but more simply that the national parties have aligned in such a way that most Massachusetts voters are Democrats, and they simply indulge that taste in state legislative elections regardless of the performance of the state legislature.

The implications of the mismatch problem are dramatic, as it leaves very little space for local accountability or representation. How state legislators perform in office may have a small effect on whether they get to stay in office, but, for the most part, their re-election chances will be determined by the popularity of the president. There is little reason to believe that officials who were elected because, say, the president of the same party conducted a successful war will accurately represent voter preferences on state issues. State legislatures are the workhorses of policy-making in this country, producing our contract and tort law, marriage policy, much of our criminal law, and lots more. But the content and effects of that policy don't have much effect on state elections.

This would not matter so much if there were other effective ways to ensure officials were held accountable. But there aren't. The primary electorate, which you might imagine produces accountability in states dominated by one party, is largely uninformed about the ideology of candidates or their performance (and there are no on-ballot heuristics like party labels to help them.) Some citizens "vote with their feet" and leave jurisdictions that are governed in ways they find abhorrent. This creates some accountability, but, because people have all sorts of reasons, social and economic, to continue living in a jurisdiction even if the government is performing poorly, state and local elections are still very important.

But why don't they work? We might expect out-of-power parties (Massachusetts Republicans, Idaho Democrats) to try to re-brand themselves at the state level, creating competition on state issues. But state laws and party rules make it hard for them to do so. For instance, voters cannot register in one party for national elections and another for state elections, meaning that the primary electorate and candidate base for state parties are composed of people who agree on national issues but not necessarily on state issues. This makes re-branding hard, if not impossible.

Even if some degree of re-branding occurred, voters would have to be able to differentiate state parties from their national parents. But it turns out that voters often don't know which party is in power in state elections and have difficulty figuring out whether state and national officials are responsible for policy changes. This makes it difficult to create running tallies on state issues (and one-party domination makes it harder still, as voters in a state like Idaho have no actual experience being governed by a Democratic legislature). Because we don't know much about state parties, we just rely on national party labels when voting.

Regardless of the reason, it's pretty clear that many elected officials do not face much pressure at the ballot box. What's needed are tools for creating locally-specific heuristics for voters. Previous "solutions" like non-partisan elections remove information rather than adding it, making things worse, not better.

Elmendorf and I have come up with a few ideas. Ballots could designate which party is in control of the state legislature, allowing voters to more easily decide based on policies and performance. States could mandate that ballots list candidates as, say, "Massachusetts Republicans," rather than just as "Republicans," allowing voters to more easily disassociate the state and national parties. Voter registration rules could be relaxed to allow separate membership in parties for state and national elections. More radically, states could ban national parties from contesting local elections, allowing local parties to develop, although this would face serious constitutional challenges.

In places where primaries determine the outcome of elections because of one-party dominance, we could allow third parties or other groups to make endorsements on primary ballots. In non-partisan jurisdictions, we could allow the mayor or governor to make on-ballot endorsements in legislative elections, turning the individual brand of a high-profile official like a Bloomberg into a down-the-ballot party-like brand.

The key is getting better information about legislative candidates to voters in state and local elections. Without it, these elections will continue to fail us.