-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mahalia S Desruisseaux, Tina Q Tan, Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity (IDA&E) Roadmap: Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Commitment to the Future, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 222, Issue Supplement_6, 15 October 2020, Pages S523–S527, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa153

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article identifies the major elements of the strategic road map for the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s (IDSA) Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity (IDA&E) initiative and discusses the long-term goals and the proposed steps needed to achieve these goals.

Although many medical disciplines have implemented diversity initiatives, gains have been slow in reflecting the diversity of the US population in the physician workforce (Table 1) [1, 2]. In a 2017 study by Aberg et al [3], among members of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), only 3% self-reported as black or African-American, and only 6% self-reported as Hispanic, whereas only 36% of members self-identified as women. These percentages are markedly lower than the national trends for Infectious Diseases physicians, which themselves poorly reflect the respective groups’ estimated distributions in the United States (Table 1) [1]. Over the last several years, changes have occurred in the IDSA membership so that in 2019, 41% of the members self-identified as women. The IDSA has also made significant progress in addressing the gender disparities among members serving on the Board of Directors and on the various committees. As of 2019, the current Board of Directors consists of 11 women and 4 men with 4 women serving on the Executive Committee of the Board of Directors. Women currently serve as Chairpersons of 57% of IDSA committees, subcommittees, and task forces. In addition, women made up 53% of the IDWeek 2019 faculty. However, data are lacking regarding the involvement of persons of color and underrepresented minorities in IDSA. Obtaining this information will be critical to identifying gaps and understand the changes that are needed to create equitable access to IDSA leadership positions.

Diversity in Medicine by Race and Ethnicity—Percentagesa,b

| Specialty . | Asian . | Black or African American . | American Indian or Alaska Native . | Hispanic (Alone or With Any Race) . | Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander . | Multiple Race Non-Hispanic . | Other Race/ Ethnicity . | White . | Unknown . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Physician Workforcec | 17.1 | 5.0 | 0.3 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 56.2 | 13.7 |

| Internal Medicine Womend | 29.0 | 7.9 | 0.2 | 6.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 43.4 | 11.6 |

| Internal Medicine Mend | 20.1 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 44.7 | 21.8 |

| Infectious Diseases Womend | 27.9 | 5.9 | 0.1 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 49.7 | 5.4 |

| Infectious Diseases Mene | 18.1 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 8.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 56.2 | 11.2 |

| Total US Populationf | 5.9 | 13.4 | 1.3 | 18.3 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 60.4g |

| Specialty . | Asian . | Black or African American . | American Indian or Alaska Native . | Hispanic (Alone or With Any Race) . | Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander . | Multiple Race Non-Hispanic . | Other Race/ Ethnicity . | White . | Unknown . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Physician Workforcec | 17.1 | 5.0 | 0.3 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 56.2 | 13.7 |

| Internal Medicine Womend | 29.0 | 7.9 | 0.2 | 6.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 43.4 | 11.6 |

| Internal Medicine Mend | 20.1 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 44.7 | 21.8 |

| Infectious Diseases Womend | 27.9 | 5.9 | 0.1 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 49.7 | 5.4 |

| Infectious Diseases Mene | 18.1 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 8.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 56.2 | 11.2 |

| Total US Populationf | 5.9 | 13.4 | 1.3 | 18.3 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 60.4g |

Bolded text highlights the race and ethnicity among the total US physician workforce and the total US population compared to the women and men in the infectious diseases workforce.

aPercentages by self-reported race and ethnicity of the total physician workforce and percentages of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases in comparison to the US population. Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases percentages are stratified by self-reported gender.

bAdapted from the Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019. Accessed 17 February 2020.

cTotal Physician Workforce: women, 35.8%; men, 64.1%; unknown, 0.2%.

dTotal Internal Medicine: women, n = 45 240; men, n = 72 883.

eTotal Infectious Diseases: women, n = 3915 (41.57%); men, n = 5503 (58.43%).

fUS Population: women, 50.8%. Data obtained from the United States Census Bureau. Population Estimates, July 1, 2019 (V2019). Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219. Accessed 17 February 2020.

gPercentage reflects white, non-Hispanic/Latinx. Percentage is 76.5% when Latinx and/or Hispanic included.

Diversity in Medicine by Race and Ethnicity—Percentagesa,b

| Specialty . | Asian . | Black or African American . | American Indian or Alaska Native . | Hispanic (Alone or With Any Race) . | Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander . | Multiple Race Non-Hispanic . | Other Race/ Ethnicity . | White . | Unknown . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Physician Workforcec | 17.1 | 5.0 | 0.3 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 56.2 | 13.7 |

| Internal Medicine Womend | 29.0 | 7.9 | 0.2 | 6.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 43.4 | 11.6 |

| Internal Medicine Mend | 20.1 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 44.7 | 21.8 |

| Infectious Diseases Womend | 27.9 | 5.9 | 0.1 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 49.7 | 5.4 |

| Infectious Diseases Mene | 18.1 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 8.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 56.2 | 11.2 |

| Total US Populationf | 5.9 | 13.4 | 1.3 | 18.3 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 60.4g |

| Specialty . | Asian . | Black or African American . | American Indian or Alaska Native . | Hispanic (Alone or With Any Race) . | Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander . | Multiple Race Non-Hispanic . | Other Race/ Ethnicity . | White . | Unknown . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Physician Workforcec | 17.1 | 5.0 | 0.3 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 56.2 | 13.7 |

| Internal Medicine Womend | 29.0 | 7.9 | 0.2 | 6.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 43.4 | 11.6 |

| Internal Medicine Mend | 20.1 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 44.7 | 21.8 |

| Infectious Diseases Womend | 27.9 | 5.9 | 0.1 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 49.7 | 5.4 |

| Infectious Diseases Mene | 18.1 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 8.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 56.2 | 11.2 |

| Total US Populationf | 5.9 | 13.4 | 1.3 | 18.3 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 60.4g |

Bolded text highlights the race and ethnicity among the total US physician workforce and the total US population compared to the women and men in the infectious diseases workforce.

aPercentages by self-reported race and ethnicity of the total physician workforce and percentages of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases in comparison to the US population. Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases percentages are stratified by self-reported gender.

bAdapted from the Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019. Accessed 17 February 2020.

cTotal Physician Workforce: women, 35.8%; men, 64.1%; unknown, 0.2%.

dTotal Internal Medicine: women, n = 45 240; men, n = 72 883.

eTotal Infectious Diseases: women, n = 3915 (41.57%); men, n = 5503 (58.43%).

fUS Population: women, 50.8%. Data obtained from the United States Census Bureau. Population Estimates, July 1, 2019 (V2019). Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219. Accessed 17 February 2020.

gPercentage reflects white, non-Hispanic/Latinx. Percentage is 76.5% when Latinx and/or Hispanic included.

Studies show that diversity in business organizations, including racial and gender diversity, inform how individuals approach complex tasks and experiences, leading to superior outcomes, including better problem solving and innovation [4–6]. This principle also holds true in medicine. In a recent study, Dr. Marcella Alsan et al [7] reported that a racially concordant physician-patient relationship was associated with a 19% reduction in the black-white male gap in cardiovascular mortality. How can we then institute diversity-enriching practices that will allow us to reach membership and leadership profiles that better represent our discipline and the population at large, so that we can truly fulfill IDSA’s mission to “improve the health of individuals, communities, and society by promoting excellence in patient care, education, research, public health, and prevention relating to infectious diseases?”

In 2018, The IDSA Board of Directors approved the launch of a diversity, inclusion, and equity task force [8], later renamed the Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity (IDA&E) Task Force [9], which was tasked with developing guiding principles that would help ensure that the Society’s board of directors, leadership teams, and committee structures reflect the diversity of its membership [8]. This task force was chaired by an IDSA board member, Dr. Tina Tan, and included the following members: Drs. Lillian Abbo, Maria Alcaide, Jose Caro, Mahalia Desruisseaux, Raul Macias Gil, Janet Gilsfdorf, Ravina Kullar, Jasmine Riviere Marcelin, Katherine Moyer, Damani Piggot, Dawd Siraj, and Manal Youssef-Bessler [8]. To help the task force reach its goal, IDSA engaged Diversity & Inclusion consultant, Vernetta Walker, JD. With the adoption and acceptance of the guiding principles of IDA&E as a core value, IDSA embarked on a new chapter to incorporate the principles of IDA&E into all levels of the organization. One of the major goals of the task force was to create a roadmap to provide clear guidance on IDSA’s efforts to promote and sustain diversity.

INCLUSION, DIVERSITY, ACCESS, AND EQUITY ROADMAP

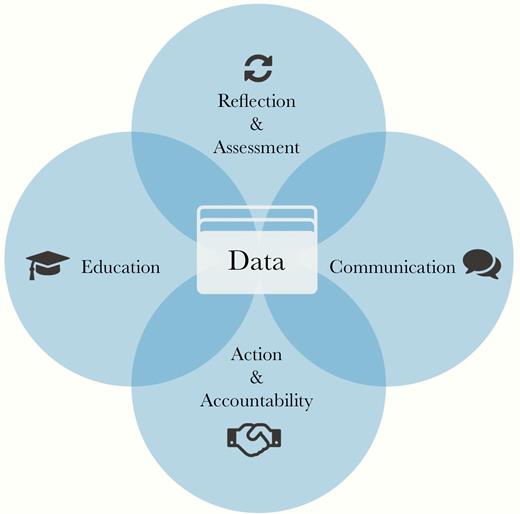

With the goal of providing transparency, education, and raising awareness, the IDA&E Task Force identified 5 pivotal intersecting action areas that the Society could prioritize to drive our efforts supporting diversity, inclusion, and equity. These areas are discussed below.

Data

As physicians, advanced practice providers, ID pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals, data drive our everyday decision making, particularly when they lead to paradigm shifts in our practices. The IDSA guideline updates are predicated on the premise that science evolves, and that new data can fundamentally change how we approach infectious processes both from a clinical as well as a research prospective. Thus, to fully understand where and why gaps exist in diversity in our discipline and in the Society, we need to obtain, provide access to, and act on existing and as-yet unidentified data. The Task Force underscored the vital role of data by placing it as the central point on the roadmap towards diversity and inclusion (Figure 1). Data (eg, number of IDSA members who are of an underrepresented group that participate in the IDWeek Mentorship Program and are members of the Mentorship Program Committee; number of hospitals, academic institutions, research laboratories, and private practices that offer training on IDA&E practices) will be collected from the various IDSA entities, including from staff, members, leadership, committees, and practice types. We expect that these data will identify areas that need improvement, provide accountability, evaluate progress, and potentially provide a scalable model that can be used by other institutions or organizations.

Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity (IDA&E) Roadmap graphic. Conceptualized by the 2019 IDA&E Task Force. Designed by IDSA.

Education

Because continuous learning is the backbone of how we obtain new knowledge and approach challenges, the Task Force has built a resource library (https://idsocietyorg.box.com/s/7ncvsf4gk8eakv2dp6jc1orxm7tbb6mp) replete with videos and literature on diversity in the healthcare workforce. In addition, IDSA’s commitment to education on gaps in diversity cannot be understated. In September 2017, Dr. Judith Aberg [3] reported on the challenges facing women and underrepresented minorities in the Infectious Diseases Workforce. This was followed by a dedicated supplement in 2019 in The Journal of Infectious Diseases (JID), addressing inclusion, diversity, access, and equity [10]. In continuing these efforts, JID is again dedicating a supplement on challenges and possible solutions pertaining to inclusion, diversity, access, and equity, which will be provided with open access online. The IDSA will continue in the same vein, providing resources to help identify challenging areas and helping to mitigate practices that perpetuate inequity in the Infectious Diseases workforce, in IDSA membership, on IDSA committees, and in the IDSA leadership. Over the last year, the IDSA Board of Directors engaged in 2 IDA&E training sessions to give each of the board members a chance to personally reflect and assess their understanding of the importance of IDA&E and provide education on the impact that implicit (unintended) bias can have on an individual’s interpretation of information and situations and their ability to make decisions. A workforce with a better personal understanding of how implicit bias may affect all aspects of IDA&E can create strategies that significantly lessen its impact.

Communication

It is crucial to formulate strategies that implement effective communication with IDSA members, the Infectious Diseases community at large, and the communities we serve, to ensure that information is exchanged with our membership in real time and enhance transparency in our efforts to build a diverse community. This year, IDSA launched a Digital Strategy Advisory Group [11] to advise on ways to reach the broader ID community on multiple platforms. This is not without precedent. A recent report by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) suggested that a strong social media presence significantly boosted follower engagement [12]. In the PIDS study, by increasing social media activities on Twitter (1.33 to 18 per month) and Facebook, the number of PIDS Twitter followers increased from 163 (preintervention) to 431 (postintervention), and the total number of followers increased from 1.4/week to 6.4/week. Facebook Page likes increased from 152 (preintervention) to 3295 (postintervention). This study demonstrated that an increasing social media presence resulted in reaching a larger audience and resulted in increased engagement with PIDS. The study did not look at factors of inclusion and diversity of the followers; however, this type of platform could be used to gather data on various factors on the diversity of the followers and provide information that can be used to develop means that further broaden outreach to specific groups. Thus, a collateral benefit to ensuring that data-driven information is relayed in real time to a broad audience, using multiple easily accessible platforms, is that effective communication can foster a strong sense of community and increase participation within the diverse ranks of IDSA and the Infectious Diseases community at large.

Action and Accountability

A key area of focus for the Task Force is establishing a model of accountability that can be implemented by the Society. We can evaluate the data collected by various IDSA entities to help us identify areas where gaps exist and where we can take action, using scalable and reproducible metrics. This will allow us to design measurable goals that we can use objectively to monitor progress, make improvements, or adjust strategies and priorities to achieve our goals of implementing the principles of inclusion, diversity, access, and equity at all levels of the organization. In parallel with the Task Force’s efforts, in 2019, IDSA members approved a bylaws change to replace the Nominations Committee with a Leadership Development Committee [13, 14], which was tasked with ensuring that diversity, inclusion, access, and equity principles are incorporated in the Society’s strategies for identifying and cultivating leaders and ensuring that the Society’s governance structure reflects the overall membership [14]. In concert with the efforts of the IDA&E Task Force (https://www.idsociety.org/about-idsa/governance/inclusion-diversity-access-and-equity-idae-task-force/), the Leadership Development Committee (https://www.idsociety.org/idsa-newsletter/march-20–2019/leadership-development-committee-members-named/) incorporated the guiding principles of IDA&E put forth by the IDA&E Task Force as its basis for recommending strategies for identifying and cultivating leaders to advance the Society’s strategic priorities. The development of a Slate-based election process ensures further transparency in the nominations process and allows for the development of a proposed slate of qualified candidates that are more reflective of the overall membership.

Reflection and Assessment

To allow positive evolution of the IDA&E efforts and achieve our desired goals, periodic self-assessments will be incorporated into IDSA’s programs to recognize areas in which appropriate progress is made, where gaps still exist, and where strategies need to be shifted. These data will be communicated with members to increase accountability and provide a platform for feedback and suggestions.

CONCLUSIONS

Although there are considerable discrepancies that need to be addressed, recent history tells us that measurable progress, such as that displayed by the attention to gender equity within the Society, can be achieved if a concerted effort is undertaken to actively address disparity. In 2009, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education introduced 2 Standards of Diversity for accreditation of Medical Education Programs, which required medical schools to develop policies and practices that would increase diversity in the students, faculty, staff, and other members of their academic communities [15]. With the expansion of medical school class sizes and the opening of new medical schools, there has been an increase in the number of medical school spots available. This has consequently had a positive effect in significantly increasing medical school matriculation from groups historically underrepresented in medicine without adversely affecting the number of Asian or white matriculants [16]. This is a positive step in working to decrease implicit bias and healthcare disparities among those groups that are underrepresented in medicine. This progress is particularly evident with gender diversity, where female medical school matriculants have surpassed male students since 2017–2018 [17]. Gender was specifically addressed for Infectious Diseases practitioners (both adult and pediatrics) in a collaborative report between the George Washington University Health Workforce Institute and the Infectious Diseases Society of America published in 2017 titled “The Future Supply and Demand for Infectious Diseases Physicians.” It is interesting to note that the gender distribution for adult ID practitioners was predominantly male (with the exception of physicians between 35 and 39 years of age), whereas for pediatric ID practitioners, the gender distribution was predominantly female for physicians between 30 and 49 years of age [18]. The goals of IDA&E are achievable if a committed effort is put into place to actively incorporate the IDA&E principles into all functions and levels of the Society.

Notes

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.