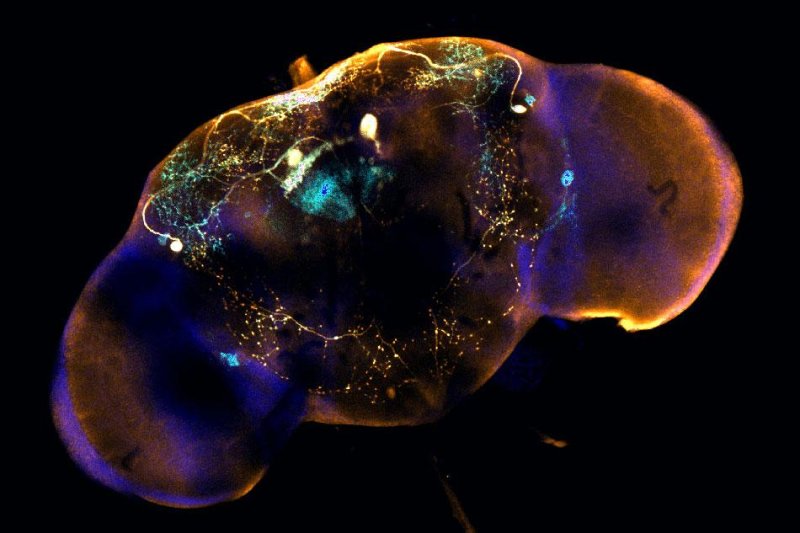

The photograph shows a fruit fly brain expressing Neuropeptide-F, or NPF. The offspring of fruit flies exposed to parasitoid wasps expressed lower levels of NPF, driving a preference for ethanol-rich food sources. Photo by Balint Kacsoh

July 9 (UPI) -- While actual memories aren't passed along to offspring, new research suggests the genetic effects of environmental stressors experienced by parents can be inherited across generations.

The findings, published this week in the journal eLife, offer a new perspective on the nature-versus-nurture debate.

"While neuronally encoded behavior isn't thought to be inherited across generations, we wanted to test the possibility that environmentally triggered modifications could allow 'memory' of parental experiences to be inherited," Julianna "Lita" Bozler, a doctoral candidate in the Bosco Lab at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, said in a news release.

For their experiment, researchers exposed fruit flies, Drosophilia melanogaster, to parasitoid wasps, which deposit their eggs into fruit fly larvae. The wasps, once hatched, kill and eat the larvae. To keep their offspring safe, female fruit flies exposed to wasps switch up their dietary habits and begin targeting food containing ethanol, which serves as a protective egg laying substrate.

Scientists collected the eggs of two groups of fruit flies. One group was unexposed, while the other was forced to cohabitate with wasps for several days. Researchers monitored the development of each group of offspring, neither of which were exposed to adult fruit flies or wasps. The offspring of fruit fly females exposed to wasps continued to show a preference for ethanol-rich food sources.

"We found that the original wasp-exposed flies laid about 94 percent of their eggs on ethanol food, and that this behavior persisted in their offspring, even though they'd never had direct interaction with wasps," said Bozler.

The second generation of fruit flies laid 73 percent of their eggs on an ethanol substrate.

"Remarkably, this inherited ethanol preference persisted for five generations, gradually reverting back to a pre-wasp exposed level," Bozler said. "This tells us that inheritance of ethanol preference is not a permanent germline change, but rather a reversible trait."

Researchers determined both male and female offspring of wasp-exposed females produced lower levels of Neuropeptide-F, or NPF. The neuronal shift encouraged a preference for ethanol.

According to Giovanni Bosco, a professor of molecular and systems biology at Geisel, the findings by Bozler and her research partner Balint Kacsoh could provide insights into the mechanisms biologic inheritance in humans and other animals.

"Of particular interest, are the conserved signaling functions of NPF and its mammalian counterpart NPY in humans," Bosco said. "We hope that our findings may lead to greater insights into the role that parental experiences play across generations in diseases such as drug and alcohol disorders."