Tomorrow, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics will release its employment numbers for the month of June, which is National LGBTQ Pride Month. Since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry in 2015, support for marriage equality in the United States has continued to grow among the public. However, LGBTQ people are still susceptible to discrimination in many areas of life and experience poverty at higher rates compared with their non-LGBTQ peers. As previous analyses have shown, traditional measures of recovery since the Great Recession in 2009 mask ongoing economic insecurity for many workers, particularly women and people of color. Post-recession economic analysis should take into account the ways in which discrimination in hiring and firing, wage gaps, workplace harassment, and other employment barriers limit economic prosperity for all workers, including LGBTQ workers. As the labor market tightens, these blind spots become increasingly important to policymakers trying to reconcile conflicting signals from tightening employment measures stagnant wage data.

Discrimination can prevent LGBTQ people from finding or keeping a job

Conscious or unconscious bias against LGBTQ applicants can prevent them from getting hired. Prior studies found evidence of bias against LGBTQ job applicants. Since it is seldom feasible to directly observe discrimination in hiring, researchers have used resume audits, in which fictitious resumes of similarly qualified applicants are submitted for the same jobs. The experimental design allows researchers to hold relevant qualifications equal across applicants and compare resumes on which LGBTQ identity might be indicated through leadership experience at LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ organizations. Studies using resumes indicating that they belong to gay men, queer women, and transgender applicants received fewer callbacks compared with resumes without any indication that the applicant was gay, queer, or transgender, respectively. A similar study compared matched pairs of women—in which one woman in the pair was transgender—finding a net rate of discrimination of 42 percent against transgender applicants.

Qualified applicants should not have to hide their identity to get a job, yet, 1 in 10 LGBTQ people reported removing items from their resume to hide their sexual orientation or gender identity (SOGI) from employers. LGBTQ people of color, LGBTQ people with disabilities, and LGBTQ young adults edited their identities out of their resumes at even higher rates, suggesting heightened fear of discrimination for subgroups within the LGBTQ community.

Workplace discrimination doesn’t end with hiring. LGBTQ people can be passed over for career advancement opportunities, and face workplace harassment at disturbingly high rates. In a 2017 study, 1 in 5 LGBTQ people reported being discriminated against because of their SOGI when being paid equally or considered for a promotion—a U.K. study describes a “gay glass ceiling,” with gay men significantly less likely to be in the highest-paid managerial positions than comparable heterosexual men; this effect was more pronounced for gay men of color. Nearly two-thirds of LGBTQ employees reported hearing jokes about LGBTQ people in the workplace, and a hostile work environment can force LGBTQ employees to quit otherwise good jobs. Hostile workplaces exist in all industries. In tech, LGBTQ employees reported experiences of bullying and public humiliation at significantly higher rates than non-LGBTQ employees in 2017. Hostile workplaces can threaten workers’ personal safety—as in the case of Sam Hall, who worked for a mining company in West Virginia for seven years, but was ultimately forced out of his job by persistent harassment.

LGBTQ people can even be fired simply because of who they are. Kimberly Hively was reprimanded for kissing her girlfriend goodbye in a car in the parking lot of her workplace, Ivy Tech Community College. In the years that followed, she experienced extensive discrimination on the job and was eventually fired. Hively filed suit, and her case eventually led to a landmark decision in which a court ruled that workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation violates federal civil rights law. While courts are increasingly interpreting Title VII’s prohibition on sex discrimination to include SOGI, most states still lack explicit protections for LGBTQ people. It should come as no surprise that more than one-third of LGBTQ people reported hiding a personal relationship to avoid experiencing discrimination.

Previous analysis looking at those who leave the labor force points to the negative economic impacts of these career interruptions, including real wage loss over time. In other words, being fired as a result of discrimination as an LGBTQ employee can bear costs beyond the initial wage drop, such as depreciated lifetime earnings.

Federal jobs data cannot be disaggregated by sexual orientation or gender identity

Currently, federal employment surveys such as the Current Population Survey (CPS) and the Current Employment Statistics Program, also known as the establishment survey, do not collect information about workers’ SOGI. The research cited above suggests that LGBTQ workers may be unemployed or underemployed at higher rates compared with their non-LGBTQ peers, but absent reliable data, it is difficult to estimate the scale of this problem or to track progress over time.

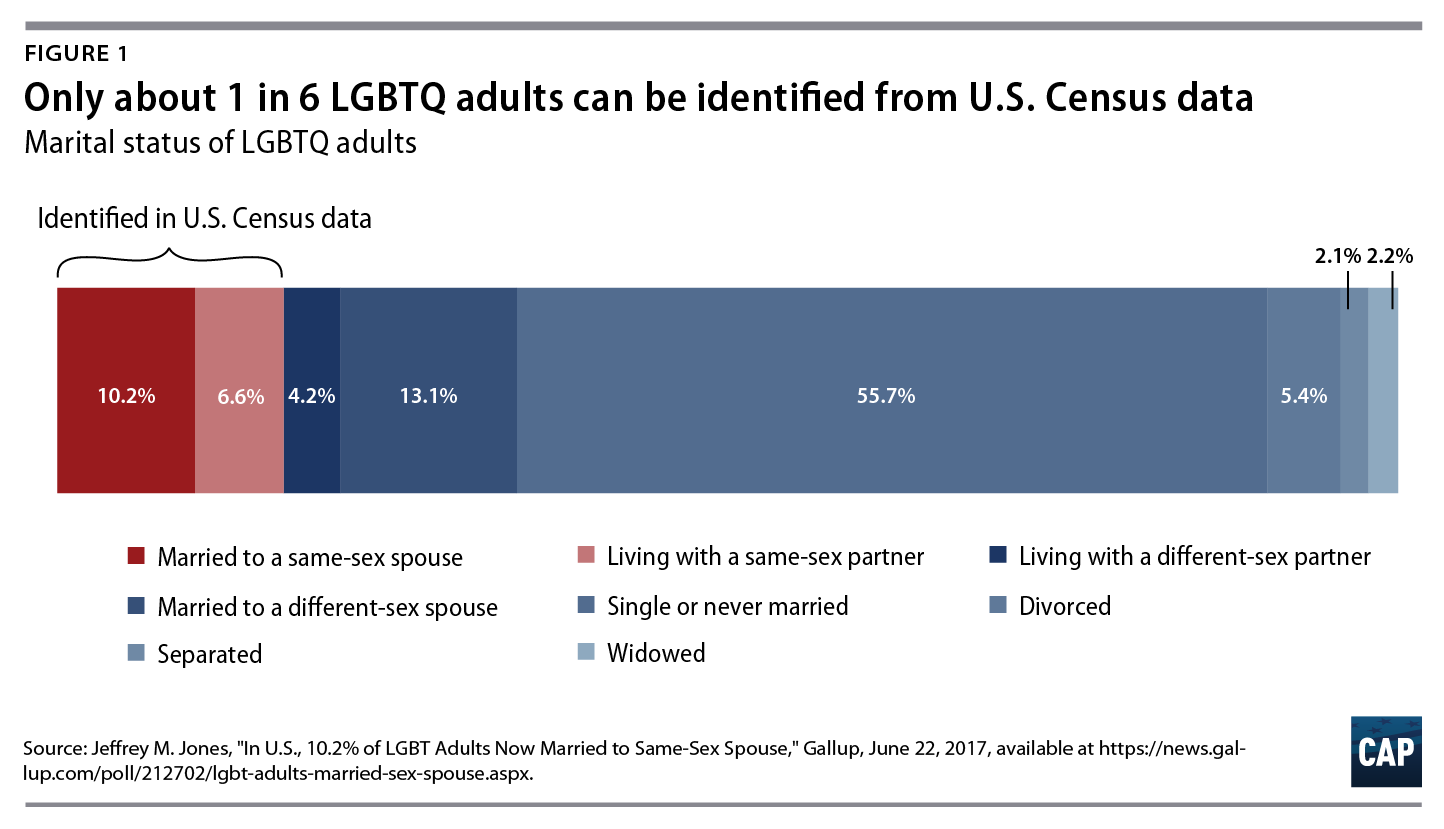

Household characteristics in the CPS and the American Community Survey (ACS) allow for comparison between households headed by same-sex couples and different-sex couples. While these comparisons offer valuable insight into the experiences of same-sex couples, such findings are not necessarily representative of the wider LGBTQ community. According to Gallup polling, as Figure 1 indicates, just under 17 percent of LGBTQ adults are considered in this analysis. LGBTQ adults are in fact more likely to be married to a different-sex spouse, which researchers attribute to the fact that roughly half of all LGBTQ adults are bisexual. Those who are single/never married—the vast majority of LGBTQ adults—as well as those who are divorced, separated, widowed, or in a different-sex couple cannot be identified from the available data. Since single individuals struggle more in the economy than married couples, it is likely that any comparisons between same-sex and different-sex couples display more positive projections than would otherwise be if the entire LGBTQ population had been included.

Not only does the U.S. Constitution mandate accurate counts of the population, the decennial census is used to determine federal funding allocations and to ensure service providers have the right resources in place to meet the needs of individual communities. It is of utmost importance to properly count and consider vulnerable populations, especially since LGBTQ people are more likely to need access to programs such as social security, public housing, and nutritional assistance.

Prior studies have found that respondents are likely to understand and respond to SOGI questions on surveys, and the low nonresponse rates for SOGI questions are comparable to questions about personal or household income. Yet, few federal surveys collect SOGI data, which significantly limits the scope of any analysis on the employment characteristics of the LGBTQ population. Recent research sponsored by the U.S. Department of Labor “did not identify any significant issues that would make collecting SOGI information in the CPS infeasible,” though adoption of such questions is pending further study.

The lack of data on LGBTQ workers poses challenges for measuring progress

The present analysis uses CPS data to offer insights into labor market security for same-sex couples. Same-sex couples are identified as married or cohabitating partners of the same sex living in one household—as identified by IPUMS family interrelationship variables.

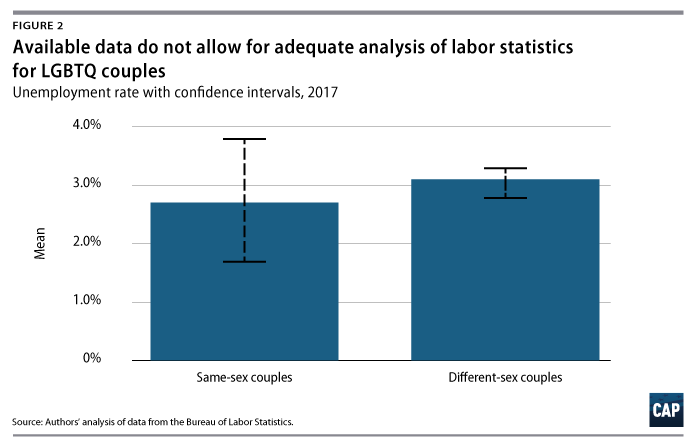

Using Annual Social and Economic Supplement CPS data for 2017, different-sex couples had an unemployment rate of 3.1 percent (defined as at least one partner or spouse in the couple being unemployed), which appears to be higher than the estimate of 2.7 percent for same-sex couples. However, the small sample size for same-sex couples (790 households headed by same-sex couples out of 56,592 households headed by any couple) creates a less certain estimate for the unemployment rate. Figure 2 below includes black bars showing the 90 percent confidence intervals for each estimate—the wider the black bar, the less certain the threshold. The much larger confidence interval for same-sex couples makes any conclusion about the actual unemployment rate less certain.

The small sample also makes it more challenging to develop estimates of the unemployment rate for subgroups of same-sex couples based on race, marital status, age, education, or other characteristics. Previously, Alyssa Schneebaum and M. V. Lee Badgett have found that same-sex couples experienced poverty at higher rates compared with different-sex couples with similar characteristics, using the much larger ACS data set. The small sample of same-sex couples in the CPS does not allow for a more nuanced comparison between same-sex and different-sex couples who are similar in age, educational attainment, and other characteristics. With a larger sample, a model that controlled for these variables may find that same-sex couples are expected to have a higher unemployment rate than comparable different-sex couples.

The findings also show gender and race disparities in household income among same-sex couple households, in line with existing literature on income gaps by race and gender. On average, since 2010, median household income for same-sex female couples was about 75 cents to the dollar compared with same-sex male couples. Similarly, same sex households in which at least one spouse or partner was a person of color made about 73 cents to the dollar compared with their white counterparts. When looking at households where both the head of household and their spouse or partner are people of color, the gap is even wider.

This analysis aggregates Asian, Black or African American, and nonwhite Hispanic couples as people of color couples, though the data suggest wage discrepancies between these different racial groups. It is important to note that the small sample sizes—for example, the CPS surveyed 531 female same-sex couples and 319 people of color same-sex couples in 2017—contribute to large variations in estimates from year to year. More data are needed to make fair and accurate conclusions about these populations.

The unemployment rate is at prerecession levels, but other labor market health indicators have yet to recover fully

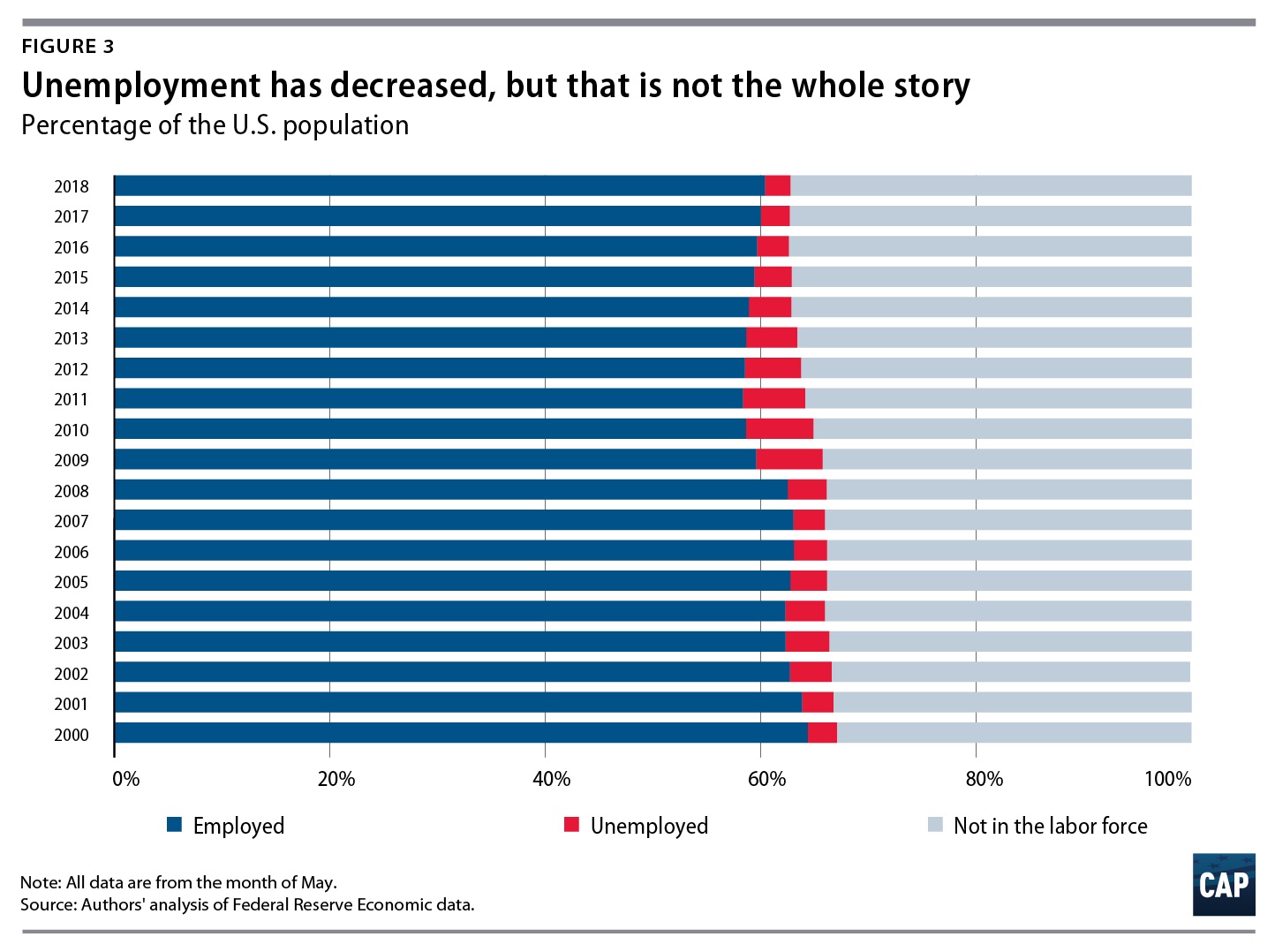

President Donald Trump inherited a growing economy; however, there is still room for additional and inclusive growth. When looking at the labor market across sexual orientation—in other words, including different- and same-sex couples—although the unemployment rate is at prerecession levels, Figure 3 indicates that the employment rate remains below prerecession rates, meaning that a larger percentage of people who would have otherwise wanted a job fall outside of the labor market now than in 2006. Unfortunately, small sample sizes limit the ability to analyze the employment rate for same-sex couples for the same time period. This drop likely indicates that some people who have exited the labor market—such as after experiencing long-term unemployment have not yet re-entered. Importantly, the number of long-term unemployed workers has continued to fall, but policymakers have work yet to do to bring everyone who might want a job back into the workforce. A recovery that reaches these workers is a key to long-term economic growth. Furthermore, although the national unemployment rate may be low, this indicator can tell a different story for other demographic groups. Indeed, the substantial lack of proper data for these populations including, but not limited to, LGBTQ individuals makes it difficult to assess whether they are included in the recovery.

Conclusion

Traditionally reported measures of growth fail to capture the needs and challenges for all American workers. Measuring recovery by the unemployment rate does not capture the economic security of people who have left the workforce since the recession. This may include workers who have been pushed out of jobs due to workplace discrimination, including LGBTQ workers. Current data limitations do not allow for an accurate measure of disparities for LGBTQ workers—or to track progress over time. Monthly employment statistics cannot be disaggregated by SOGI, and the sample of same-sex couples in the present analysis was too small to make meaningful comparisons to different-sex couples. More comprehensive data collection in federal surveys is needed for deeper analysis on the LGBTQ community, particularly for subpopulations who may face additional labor market barriers based on their gender, race, or other intersecting identities. Policymakers and economists need to consider these challenges when evaluating the health of the labor market and implementing policies that affect it.

Shabab Ahmed Mirza is a research assistant for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress. Daniella Zessoules is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center. Galen Hendricks is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center. Michael Madowitz is an economist at the Center. Laura Durso is vice president of the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center.