Ali Ibrahim, a Sudanese man who spent three years in Libya trying to cross the Mediterranean, describes it as a place of utter lawlessness.

The country is in the middle of a civil war and run by rag-tag groups of militia who treat migrants like prey.

Young men like Ali live in constant fear of being attacked or mugged.

“There are guns everywhere,” he explains. “Maybe [someone] might take your shoes. If you wear Nike, Adidas or something good like this he’ll take them.”

Ali worked in a market, pushing a wheelbarrow for customers. But he says though the women would always pay him, the men often wouldn’t.

Muzammil was taken advantage of too, his uncle says. Once he was forced into a car by three armed men who took him to a building and told him to clean it but never paid him.

Sometimes it all works out though. Ali is now settled in France after successfully crossing to Malta on his second attempt.

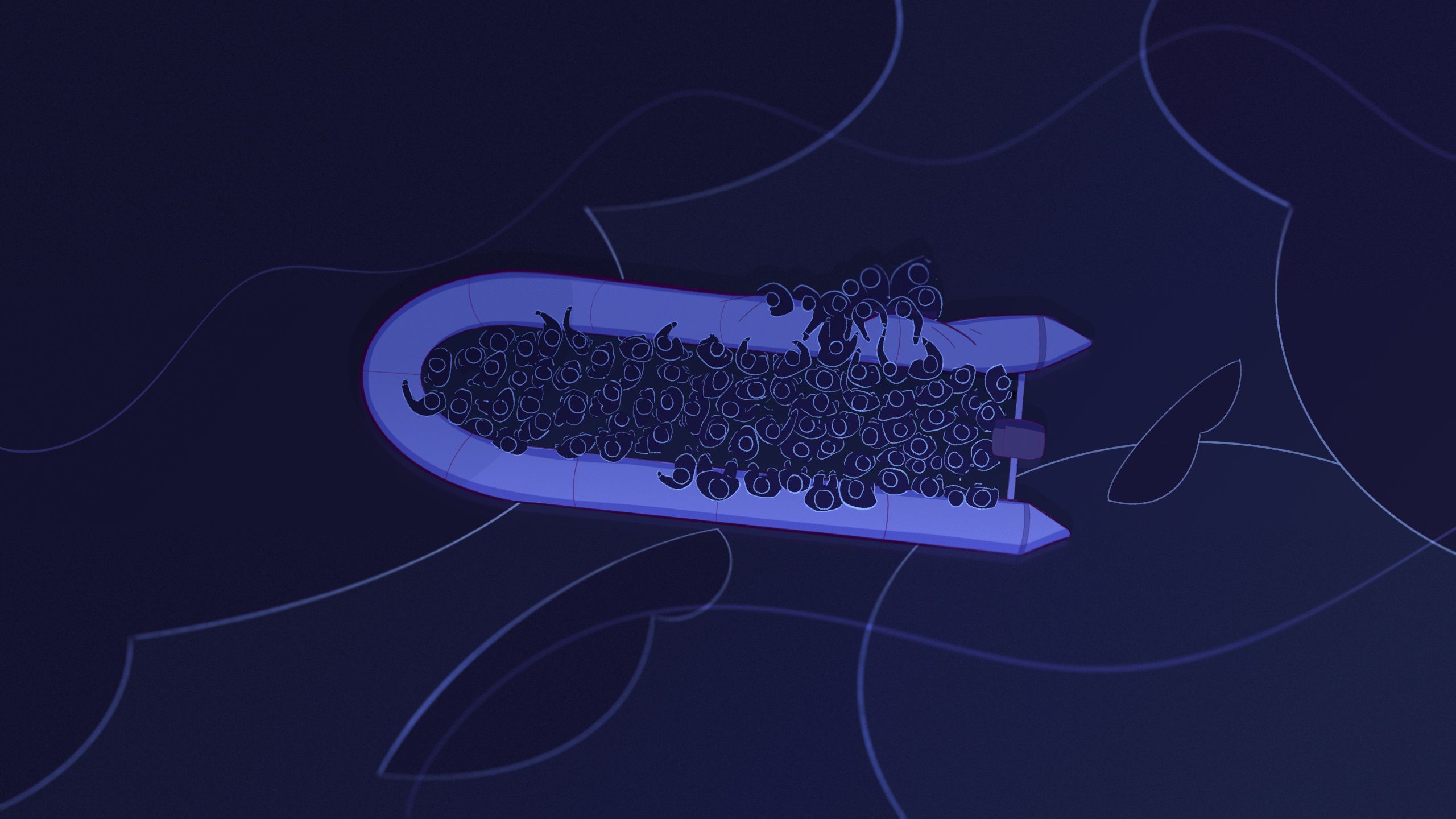

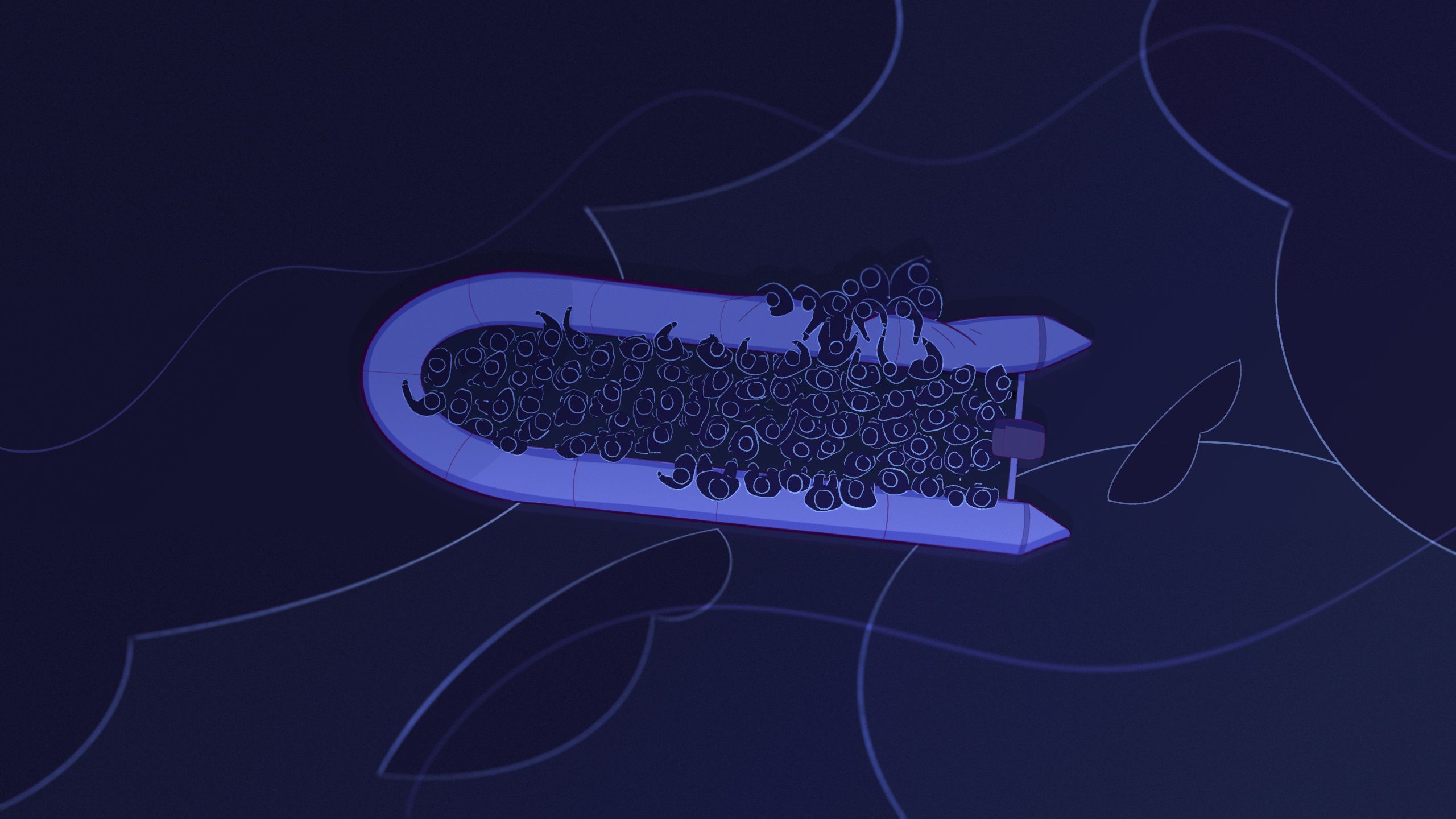

“The sea is like a drug,” he says. “Like an addiction.”